The story of a movie that was first commissioned, then censored, and finally rediscovered.

Listen to a recording of the presentation:

Youssef Chahine’s enchanted beginnings

Youssef Chahine is one of the most remarkable Arab filmmakers. He was born in 1926 in Alexandria, a historical Egyptian city and a vibrant turn-of-the-century cosmopolitan carrefour. People of all nationalities and backgrounds could be found there: Greeks, Italians, French, English, and Lebanese. Chahine grows up in the midst of this cultural effervescence that will have a long-lasting mark on his personality and career.

During his teenage years, the young Chahine is fascinated by American cinema at the beginning of its golden age. At the same time, the relative prosperity of Egypt in a region ravaged by war, creates favorable conditions for the rise of a local film industry. Quickly it becomes a booming industry that is unrivaled in the whole Middle East. During these transformative years, Chahine will evolve between two film universes: Hollywood and Cairo. These two influences will stay with him forever.

At just 21, he decides to pursue his dream of becoming an actor and starts a long journey to the United States to join The Pasadena Playhouse, dubbed “the star factory in California”. But not having the right physique, and money running out pretty quickly, he has no choice but to return to Egypt after only two years at the US West Coast. Upon his return from Los Angeles, the now 23-year-old begins his career in an already booming industry. There is popular demand for musicals and melodramas; and the young filmmaker goes along with this trend. He releases his first movie Daddy Amin a year later (“Bābā Amīn”-1950), a comedy-drama. A dozen iconic genre films will ensue, propelled by – until this day – indelible songs which are performed by the most beautiful voices of the time such as Farid al-Atrache, Shadia or Laila Murad.

Image: Yousseff Chahine, © unknown author

The late 1950s and early 1960s bring change. Chahine, in his thirties, is in search for more substance, more political depth. It is also during this time that the world witnesses an unprecedented wave of liberation movements that reaches the Arab world. Nasser, the iconic president of Egypt since 1956, understands very well the impact cinema can have in relaying and amplifying the nascent voice of the so-called “third world”. He decides to nationalize the cinematographic industry in Egypt and engages in state-sponsored massive film productions to embody his vision.

Fervently, and perhaps a bit candidly at first, Chahine whole-heartedly endorses the values of Nasserism: a progressive and egalitarian pan-Arab society. But soon thereafter he will be confronted by the limits of these ideals.

Pan-arabism and Nasserism

The Nile’s story in Egyptian cinema begins in the early 1960s. Gamal Abdel Nasser, the iconic president of Egypt since 1956, wants to embark on a pharaonic project that would embody his dream of a new, modern and independent socialist nation. The task will be the construction of the High Aswan Dam aiming at better controlling the Nile’s waters in order to boost agricultural production in addition to generating electricity.

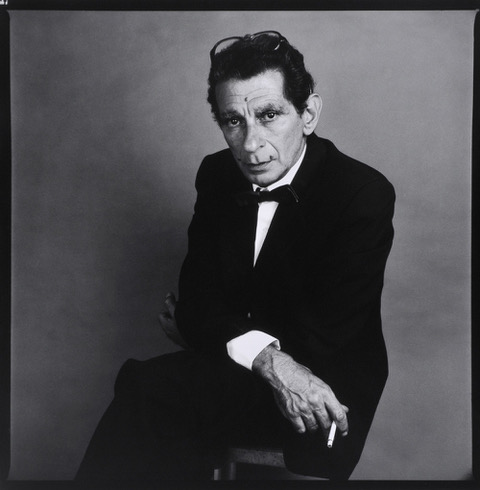

Nasser already knows the impact Egyptian cinema can have in echoing his grand vision. In fact, in 1963, the president funds “Saladin”, a historic movie celebrating the retake of Jerusalem from 12th century crusaders. It is then that the leader reaches out to Youssef Chahine for the first time, a talented young Egyptian filmmaker who was well acclaimed for his musicals and melodramas. Released a few years after the tripartite Suez Canal aggression against Egypt, “Saladin” aspired to incarnate a winning post-colonial nation in its fight against the coalescing imperial powers.

Image: Youssef Chahine, © Unknown author

After the immense success of the film, Nasser and the Soviet Union request from Chahine to direct another film that would celebrate the inauguration of the Aswan High Dam and promote the collaboration between the two allied socialist nations. The movie “Once upon a Time … the Nile” is born! (“al-Nīl wa al-Ḥayāẗ” in Arabic, which literally means “Nile and life”).

It’s 1964, during the height of the Cold War, a period in which controlling the political discourse is of utmost importance. The two coproducing nations dictate tightly their guidelines to the film director. Amongst many supervisory actions, Chahine is provided with supporting archival and documental films spanning the Dam’s construction period. The music in these films is solemn and orchestral, deliberately expressing the glory of a new socialist era.

But despite this tight oversight, the first version of the movie is not to the taste of its sponsors and is consequently banned. Perceived more as a nostalgic and melancholic depiction of the Nubian region, the movie is deemed too personal and off-topic. Indeed, Chahine willingly disobeys the officials’ recommendations, ending up making a more personal film that shows, with more objectivity perhaps, the symbolic place the river occupies in the lives of peasants.

By doing so, the film director dilutes the initial intent into a more poetic and lyrical substance emptied from any political agenda.

In the end, both Moscow and Cairo ban the first version of the film. The negatives of the film are destroyed and Chahine is summoned to remake the entire movie with a new script and a new cast of actors. The second version, renamed “Those People of the Nile”, is a film that Youssef Chahine himself will reject from his legacy.

While the first version is thought to have completely disappeared, the director manages to send the one and only positive copy secretly to Paris, in a diplomatic bag to be handed to Henri Langlois, founder of the French cinematheque. Thirty-five years later, the original work will be entirely restored in France, for a new release in 1999.

The disagreement around the depiction of the Aswan High Dam and the Nile marks the first time Chahine is personally confronted to censorship. After sincerely believing in Nasser’s egalitarian ideals, he turns his back to the regime propagandist methods and becomes a virulent critic of the one-party system. His cinema evolves too, in search for more authenticity and simplicity, features that he will find in the traditions and lives of everyday Egyptians.

Image: Aswan Dam, 1965 © Wikimedia Commons.

The disillusion and dissidence

Chahine will continue to celebrate the Nile and its peasants. In fact, only a year after “Those People of the Nile”, he produces “The Land” (“Al-ʾarḍ” -1969), a movie, considered by many critics as one of the best Arab films ever made. In it, he pays tribute once again to his beloved river, the only cause for life in the Egyptian desert. He shows the world how the river is not simply a source of water and food, but first and foremost a source of dignity and pride for the millions of villagers who live along its banks. Breaking with the grandiose western musical backgrounds, the music is more sober, willingly closer and more faithful to the local folklore. A perfect example of this can be found in “al-ʾarḍ law ʿaṭšāna”, an emotional musical theme which punctuates the tragic story of the film.

Listen:

If the land is thirsty… we will irrigate it with our blood. […] الأرض لو عطشانة نرويها بدمانا عهد وعلينا امانه تصبح بالخير مليانه

O! land of ancestors… you are our reason for being… […] we sacrifice ourselves so that you are never thirsty. يا أرض الجدود يا سبب الوجود ه نوفي العهود بروحنا نجود وعمرك م تباتي عطشانة..

In these melodies, the filmmaker also references the many gifts of the holy river with of course, on top of the list, cotton, the country’s top resource until 1973. He pays a remarkable tribute to the famous popular anthem “Nawwart yā quṭn al-Nīl” during a scene in which peasants harvest this crop.

Listen:

O blooming Cotton of the Nile O sweety and beautiful نورت يا قطن النيل… يا حلاوة عليك يا جميل..

Nawwart yā ’uṭn al-Nīl Yā ḥalāwa ʿalīk yā ǧamīl

Harvest O girls of the Nile There’s nothing like our cotton اجمعوا يا بنات النيل يلا… دا مالوهش مثيل قطن ما شاء الله

’iǧmaʿū yā banāt al-Nīl yallā dā mā lūhšī maṯīl ’otn mā šāllah

Conclusion

After a stellar career launch during the golden age of Egyptian musical-cinema, Youssef Chahine enters a new politically engaged phase at the end of the 1950s with the advent of the new Egyptian Republic. While sincerely embracing the progressist values of Nasserism at first, his cinema, and the music that embodies it, appear in a new light marked by a more openly critical tone. The grandiose orchestral moments are ditched in favor of indigenous musical references that call for authenticity, self-criticism, and reform. In doing so, Chahine will forever transfigure the codes of Arabic musicals, reinventing a music that embodies engagement in its core.

Review

The Nile and the Aswan High Dam in Youssef Chahine’s Cinema

Yasmine Hussein

Amal Guermazi’s essay takes us on a journey through one of the most politically charged and artistically agitated moments in Egypt’s modern cultural history. Reading her piece feels like following the rhythm of the Nile itself. Moving between Chahine’s evolution, film narrative, political context, and the sonic dimension of modernity, Guermazi shows how music became both an instrument of power and a refuge of resistance. Within the broader Nile Pop project, her work stands out for how it listens to the river — revealing in its soundscape the true stories of this period.

What distinguishes Guermazi’s approach is her background as a musicologist and her sensibility as a musician. She listens to Chahine’s cinema through sound — treating songs, motifs, and even silence as historical evidence. This shift from vision to audition gives her essay its originality and makes it closer to how Egyptian audiences actually experience these films.

The essay highlights Chahine’s relationship with the Nile and with music. Guermazi begins by Chahine personal history, his early years in cosmopolitan Alexandria and his brief experience in Hollywood to explain his primary artistic choices. These early influences would later crash in front of a changing Egypt. The turning point arrives with Once Upon a Time… the Nile (1964), commissioned to celebrate the High Dam and Egyptian–Soviet friendship. Guermazi recounts how Chahine’s first version — a tender, human portrait of Nubia and the river — was censored and destroyed for not aligning with the official narrative. This rupture, when he secretly trafficked the surviving copy to Paris, marked his personal letdown with state control. Guermazi then connects this moment to The Land (1969), where Chahine abandons orchestral music for the folkloric songs. Here, music itself becomes a statement where the Nile no longer sings of triumph, but of endurance, sacrifice, and belonging.

The story of Once Upon a Time… the Nile is not only about censorship; it also fits within the “cultural hydro-hegemony,” the way states use art and culture to legitimize control over land, water, and national imagination. Through music, cinema and spectacle, the river was nationalized — its natural flow made to follow the rhythm of the modern state vision. Chahine’s conflict with censorship was, in that sense, one drop in a larger river of struggle.

Yet his break with the regime was not a rejection of Nasserism itself, but only of its institutional rigidity. He refused to be Nasser’s voice, but he remained faithful to Nasser’s ideals of justice, independence, and dignity. As Guermazi highlights the metamorphosis of his musical language in The Land, one can sense how this shift resonated with the Egyptian Ministry of Culture’s own cultural policy under Tharwat Okasha in the same time. During those years, the Ministry produced a series of LPs that documented Egypt’s regional musical heritage — titles such as The Folk Music of Egypt (1967) and Nubia: Folk Melodies (1967), made in collaboration with Sono Cairo, gathering songs from the Delta, Upper Egypt, and Nubia to present the “voice of the people”. In this light, Chahine’s turn from orchestral music to the popular song was reclaiming his own Nasser promise through the people’s own voice.

Guermazi’s essay also reminds us of how Chahine’s metamorphoses resonated with Egyptian audiences. The Land, in particular, became one of the most important and popular films of Chahine. Through his art the Nile return to be a living presence that intertwined with daily life and struggle rather than a symbol of the national progress. In that sense, Guermazi’s reading bridges the space between state narratives and popular emotion, showing how art both shapes and is shaped by people.

Still, while Guermazi captures Chahine’s lyrical sensitivity to peasants and to the river, the Nubian melodies with its displacement, languages, and musical memory remain mostly a background muted music. That silence, too, is part of the Dam’s legacy: a developmental project that submerged both land and memories. Reading the essay today invites us to listen again, to hear what the soundtrack could not hold — the voices drowned by the dream of modernity that need to be recognized to celebrate their sacrifice. Revisiting this film today reopens questions of representation that remain unresolved in Egypt’s cultural landscape and it echoes several archival projects that the cultural society works on later.

Guermazi’s work opens space for further reflection. Future research might explore how later Egyptian artists continued to struggle with the Nile stories between fear, power, memory, dignity and repossession. Finally, her essay reminds us that the story of the Nile is not only written in treaties, infrastructures, mega projects or archives, but also in melodies, silences, and images — in the emotional ways Egyptians continue to imagine freedom flowing across the desert of home.