The story of the Egyptian temple of Taffeh, from the Nile Valley to the Netherlands, between archaeology and diplomacy.

Listen to a recording of the presentation:

The main hall of the Rijksmuseum van Oudheden (National Museum of Antiquities) in Leiden, the Netherlands, is graced by a a temple from Egypt. The story of the building spans two millennia. The episode of the temple’s departure from Egypt is closely connected to the river Nile, and man’s efforts to harness the power of its water. Before the temple was moved to the Netherlands, it was situated in the south of Egypt, an area called Nubia. It was located near the town of Taffa, on the banks of the river Nile. For centuries, the region of Taffa was one of the most densely populated and prosperous parts of Nubia; a crossroads of various cultures. In Taffa, fields with palms and sycamore trees stretched along the river. Between the houses one would stumble upon physical remains of a distant past. All of this was to disappear under the water of Lake Nasser. Today, the town of Taffa no longer exists, but its temple is still is a meeting place for many different people.

Image: The temple of Taffa in the main hall of the Rijksmuseum van Oudheden in Leiden. © Rijksmuseum van Oudheden.

Sanctuaries on the Nile

Image: The centre of this capital is decorated with the flower of the goddess Isis. © Rijksmuseum van Oudheden.

Image: Four decorated columns supporting the roof of the temple. © Rijksmuseum van Oudheden.

Image: The lintels of the central entrance of the temple decorated with cobras and winged sun disks. © Rijksmuseum van Oudheden.

Image: The niche in the rear wall of the temple, marking the holiest of holies of the temple. © Rijksmuseum van Oudheden.

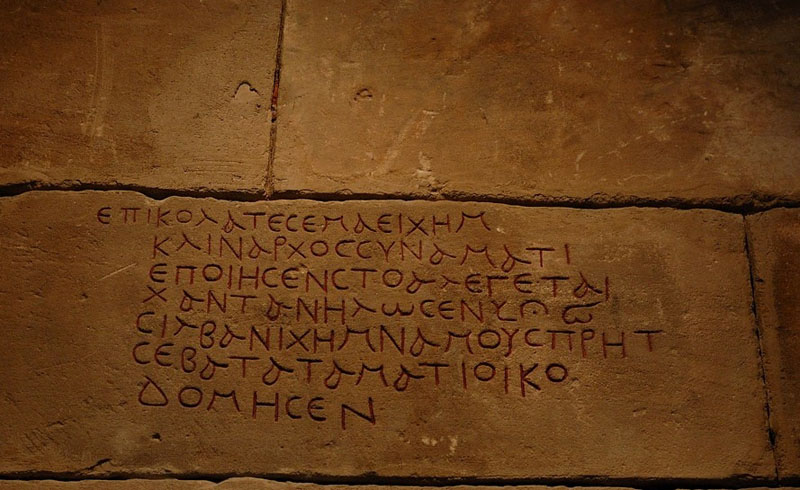

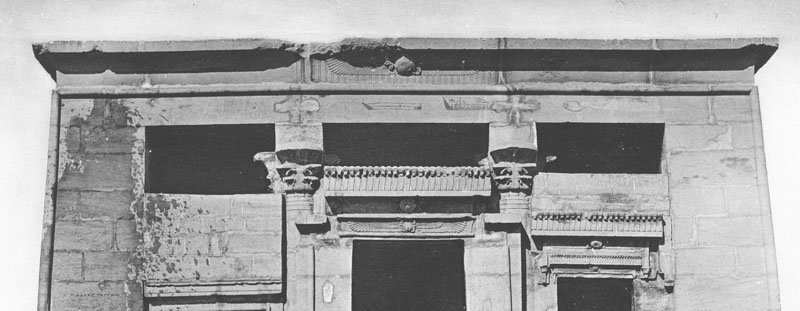

When the temple was constructed in the first century CE, the builders never completed the decoration of the chapel. Some of its details were added in more recent times and parts of the temple were restructured through time. Change, in fact, is a recurring theme in the long history of this building. There is an inscription above the offering niche that probably records adjustments to the temple. This text dates from the second half of the fourth century CE, when ancient Taphis was part of the Nubian kingdom of the Blemmyes. The text mentions a local ruler who commissioned the restoration of a temple, perhaps the temple of Taffa itself. If that is true, the temple may have been in some state of dilapidation or in need of refurbishment at that time. Indeed, the temple was extended during the third century CE and the façade was remodelled during the second half of the fourth century CE.

Image: The Greek inscription on the rear wall recording the refurbishment of a temple. © Rijksmuseum van Oudheden.

A temple transformed

Not much later, around the end of the fourth century CE, the cult of the goddess Isis was abandoned, but the temple continued to be used as a sacred space. We know that the building was transformed into a Christian church thanks to a monumental inscription found close to the original site of the temple. The church was inaugurated in 710 CE by king Merkourios, ruler of the Nubian kingdom of Makouria. Some years prior to this event, the king had managed to unite Makouria with the Nubian kingdom of Nobatia. As the sole ruler of the large Christian state, Merkourios had several churches and monasteries built. In Faras, a Nubian city that flourished at the time, the king had the great cathedral enlarged. At Taffa, the temple was altered to accommodate its new function. An entrance was cut in the lateral wall of the building in accordance with symbolism of Nubian churches. Open spaces between the original doorways and ceiling were filled up, and the walls were plastered and decorated with portraits of saints. Small holes were cut in the ceiling for the chains from which oil lamps were suspended, and in the façade, a space was cut out for a basin that would hold the holy water. Several graffiti on the walls, some in the form of small crosses, attest to the Christian services that took place in the building for some 600 years.

Image: An additional entrance cut in the east wall of the temple when it was transformed into a temple. © Rijksmuseum van Oudheden.

Image: Graffiti on the outer temple walls depicting riders and quadrupeds. © Rijksmuseum van Oudheden.

Image: Vertical grooves in the outer temple walls resulting from the practice of scraping out stone powder for magical practices. © Rijksmuseum van Oudheden.

Image: Boats painted on the lintel of the temple. Photographed on 2 January 1908. Photo: Detail of G. Maspero, Rapports relatifs à la consolidation des temples, Vol. II, pl. LII.

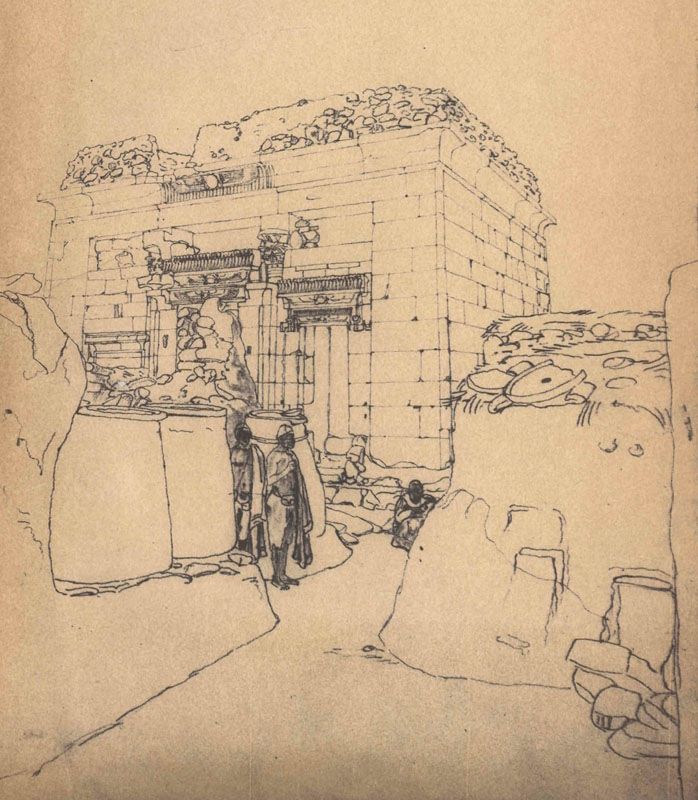

Image: Ceramic jars in front and mudbrick structures around and on top of the temple, 1826-1827. Drawing by Edward Lane.

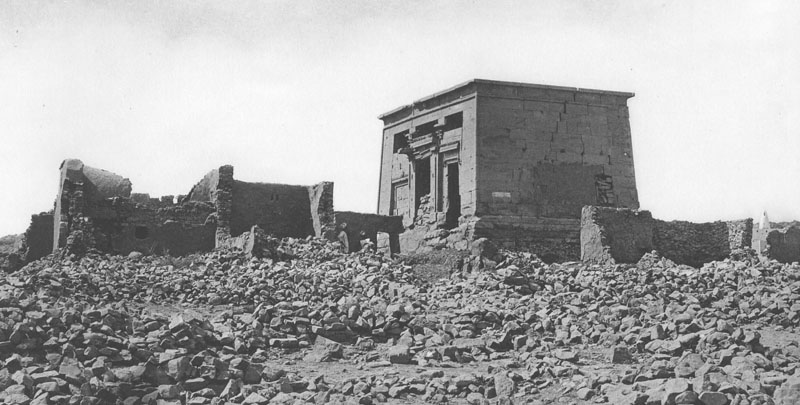

Image: The surroundings of the temple on 20 October 1907, before consolidation

work directed by Alessandro Barsanti. Photo: G. Maspero, Rapports relatifs à la consolidation des temples, Vol. II, pl. XLIX.

Villages become archaeologic sites

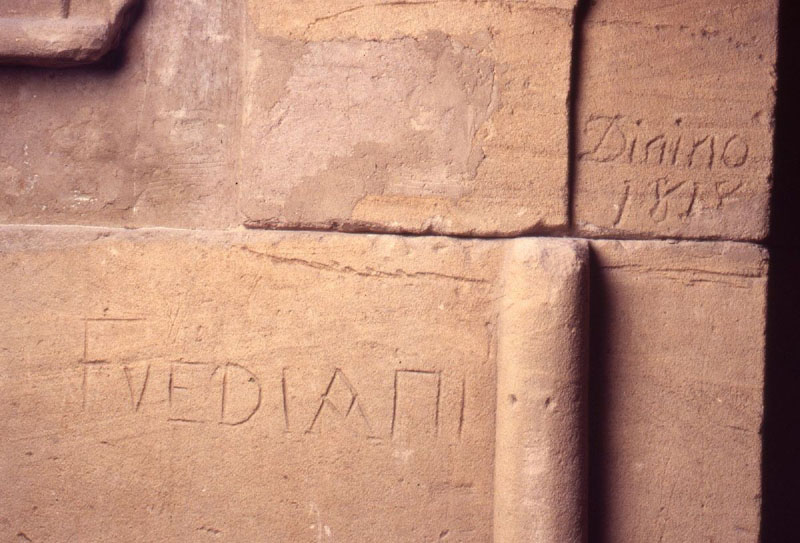

The Danish traveller Frederik-Louis Norden, who visited Taffa in 1737, was one of the first Westerners to have published on the temple of Taffa (Norden, 1755). Many more would follow in the 19th century, when European political and cultural influence in Egypt increased. After Napoleons invasion of the country, an academic interest in the ancient history of Egypt developed rapidly and thanks to the efforts of Europeans like Jean-François Champollion and Thomas Young, hieroglyphic inscriptions became increasingly intelligible. Numerous scientific expeditions were launched from Europe, travelling up the Nile to visit, record and study the ancient monuments of Egypt and Nubia. At Taffa, such visits sometimes led to clashes with the villagers who lived around the remains of the ancient site (Schneider, 1979). Still, European travellers and explorers like Jacob Burckhardt, Giovanni Battista Belzoni, Robert Hay, Edward Lane, Jean-Jacques Rifaud and Amelia Edwards made their way to the Nubian town and often published accounts of their impressions. Some 19th century visitors commemorated their visit by incising their name or initials into the walls of the temple. A traveller called Andrea Didino left his family name and the year of his visit in 1818 just below the lintel of the main entrance. Next to it is the family name of Domenico E. Frediano, who had visited various Nubian temples between 1817 and 1821 (Raven, 1999).

Image: The southern temple of Taffa at the bank of the river with the northern temple in the background. Drawing by Frederik-Louis Norden.

Image: Graffito in the temple façade left by early 19th century travellers from Europe. © Rijksmuseum van Oudheden.

The 20th century story of the temple is well documented (Schneider, 1979). In 1907, the building had to be consolidated to protect it from the Nile water. For most of the year, it would disappear in the reservoir of the Aswan Low Dam, constructed at the turn of the 20th century. But more Nile water would threaten the edifice. After Egypt had gained independence in 1952, the new government soon adopted plans for a second dam, the Aswan High Dam, which is still operational today. Construction work began in 1960. The dam would regulate the inundation of the Nile river and generate hydroelectricity necessary for the country’s industrialisation plans. As a result of the dam, an even larger reservoir was created up-river, nowadays known as Lake Nasser, permanently covering miles of land, including villages and archaeological sites. About 70.000 Nubian inhabitants of the Egyptian region were forced by the Egyptian government to leave their homes. They were housed elsewhere in the ethnically-zoned towns of New Nubia. To rescue the archaeological artifacts of the area, Egypt and Sudan called upon UNESCO (Säve-Söderbergh, 1987; Scalabrini, 2019). The organisation formed an international coalition of 51 countries from Africa, the Americas, Asia, and Europe. Between 1960 and 1965, these nations collaborated to record and save much of the ancient settlements, tombs and temples in the planned affected region. The UNESCO operation famously managed to dismantle the large temples of Abu Simbel and rebuild them at a safe location nearby. The temple of Taffa was also saved from the water, but it was to be moved from the banks of the river Nile to the canals of Leiden in the Netherlands.

Image: The temple of Taffa in the summer of 1960 after it had collapsed, presumably after the roof of the temple had been hit by a boat when the temple was submerged during inundation of the Nile after the construction of the Aswan Low Dam. Photo: Centre of Documentation on Ancient Egypt, Cairo.

Image: The Aswan High Dam under construction. Photo: Fotocollectie Anefo Reportage/WikiCommons

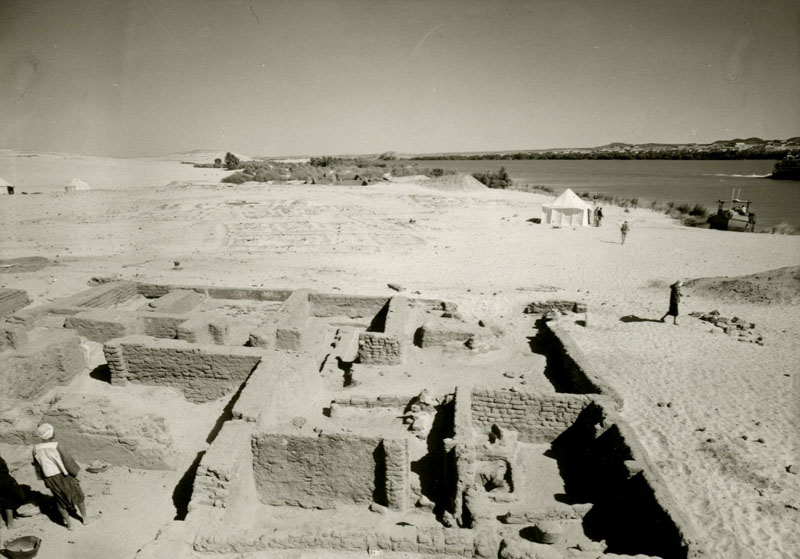

Image: Excavations at Shokan carried out by the Rijksmuseum van Oudheden © Rijksmuseum van Oudheden.

As one community gained a building from antiquity, another community lost one. For some Nubians living in Taffa, cutting the age old ties with the ancient building was a troubling experience. Christiane Desroches-Noblecourts, curator of the Egyptian collection at the Louvre Museum and in charge of the survey of the Nubian temples, recalled an encounter in Taffa with a Nubian woman in July 1964. One early morning, she and her Egyptian colleagues were confronted by a lady whom Desroches-Noblecourts described as “a sort of sorcerer”. She wore a traditional black cloak and veil and was carrying a large club. According to Desroches-Noblecourts’s account, the woman threatened them in Nubian language and wanted to prevent the outsiders from “touching our gods”. She would rather destroy them herself than see them leave (Desrouches-Noblecourt, 1992). But the Egyptian government had made its decision: the Nubian community was to be rehoused and the sanctuary of Taffa would be removed from the Nubian landscape.

The international politics of antiquities

The Netherlands was one of five countries to be granted Nubian temples and chapels by Egypt. The temple of Dabod was given to Spain, the temple of Dendur to the United States, the chapel of Ellesiya to Italy, and the portico of the temple of Kalabsha to Germany. These five countries had spent the most on the salvage campaign or had overseen most of the engineering operations in relation to the largest temples. But international politics and diplomacy also played a decisive role in the allocation of the temples. The independent Egyptian republic had been declared in 1952, and for the first time the Antiquities Service was fully directed by Egyptian officials. The Egyptian state began to use foreign interest in the archaeology of Egypt, and Nubia in particular, as leverage. In order to entice countries to join the UNESCO campaign, the Egyptian government promised to grant the contributing nations’ excavation concessions, a 50% share of the findings, and even the donation of entire Nubian temples. This approach was successful and through political and diplomatic efforts, several countries were now negotiating the bestowment of a temple. Under the pretext of international cooperation and cultural preservation, Western countries joined the campaign to protect and re-establish their primacy in the domain of the archaeology and museology of ancient Egypt. Simultaneously, the Egyptian government used international access to the monuments of the Egyptian past to exercise political power. Belgium, for example, was meant to receive the temple of Dendur. Although the country participated in the UNESCO campaign, the Egyptian state eventually donated the temple to the United States instead, because it disapproved of the country’s colonial regime in Belgian Congo.

The temple of Taffa was also a source of some contention. In 1965, the Dutch Rijksmuseum van Oudheden had submitted a request for the temple of Taffa to be moved to the Netherlands, after a request to get some parts of the temple of Derr had been denied. But another European country had tried to secure the very same building. Here, international diplomacy came into play. In 1966, it had still not been decided where the temple of Taffeh would be rebuilt, but the Netherlands actively sought to obtain it. Adolf Klasens, director of the Rijksmuseum van Oudheden and secretary of the landscaping group that oversaw the reconstruction of the temple of Abu Simbel, spearheaded Dutch talks with Egyptian officials. He was assisted by the Dutch embassy in Egypt and the Dutch Ministry of Culture, Recreation and Social Work. In September 1967, Klasens paid a visit to Sarwat Okasha, the then Egyptian Minister of Culture, to tighten the relations between the Netherlands and Egypt. At the same time, Shahata Adam, director of the Egyptian Antiquities Organisation, had already mentioned to Klasens that the temple of Taffa would go to the Netherlands.

Moving a monument

Before the temple of Taffa was moved to the Netherlands, the Egyptian government made two stipulations (Schneider, 1979). The temple had to be freely accessible to the public and should be kept at a site where it would be preserved for posterity. It would take several years before these conditions were met in Leiden. The temple of Taffa was the first Nubian temple to be rescued as part of the UNESCO salvage campaign. It was dismantled in July 1960 by a team of Polish and Egyptian archaeologists. The blocks of the temple were documented, numbered, crated and moved to Elephantine island in Aswan. There they remained until 1970, when the transfer of the blocks to Netherlands began. The sealed crates with the blocks were placed on large flat-bottomed Nile vessels, travelling from Aswan to Alexandria. The crates were then loaded on a ship called ‘De Sinon’, which arrived in Rotterdam on 18 January 1971. The very same day, the blocks were moved to a storehouse in Leiden. They were kept there until the reconstruction of the temple would begin in 1978.

Image 18: The dismantled blocks of the temple of Taffa on the island of Elephantine. © Rijksmuseum van Oudheden.

Image: The crated blocks of the temple arrive at the seaport of Rotterdam on 18 January 1971. © Rijksmuseum van Oudheden.

In order to make the temple accessible to visitors, the National Museum of Antiquities had to construct a new hall large enough to house it properly. After it had been completed, the temple blocks were transported to the museum and rebuilding could commence. The process of reconstruction was carried out under supervision of Hassan el-Ashiry. An architect by training, he had recently been appointed the director of the Egyptian Museum in Cairo. El-Ashiry had brought to Leiden the plans and documentation of the dismantled temple. Layer by layer, the numbered blocks could then be placed in their original position thanks to the expertise of the conservators of the Rijksmuseum van Oudheden. Where necessary, reconstructive elements were installed to ensure the integrity of the temple. The temple was officially inaugurated in the museum on 4 April 1979 by princess Beatrix of the Netherlands. The event was attended by Shehata Adam, the then head of the Egyptian Antiquities Service.

Image: Hassan el-Ashiry during the first phase of the reconstruction of the temple of Taffa in Leiden, 1978. © Rijksmuseum van Oudheden.

Image: The temple in scaffolding during reconstruction in the main hall of the Rijksmuseum van Oudheden, 1978. © Rijksmuseum van Oudheden.

Image: The temple during restoration by experts from the Rijksmuseum van Oudheden and specialists from construction company Burgy, 1978. © Rijksmuseum van Oudheden.

Image 23: The inauguration of the temple at the Rijksmuseum van Oudheden on 4 April 1979, attended by princess Beatrix of the Netherlands and her husband Prince Claus, Shehata Adam, Head of the Egyptian Antiquities Service, and Amin Samy, Egyptian ambassador to the Netherlands. © Rijksmuseum van Oudheden.

Today, the temple of Taffa stands at the heart of the museum and it is probably the first artifact from antiquity that meets the visitor’s eye. As the building is a space that can be entered, the visitor experiences the past in a more direct, more physical fashion than when standing in front of a show case with objects. The building also provides an important backdrop for several of the museum’s activities such as talks, graduation ceremonies, debates, symposia and artistic performances. Three times a day, a light show is projected on the temple’s façade. The show, which combines animation, music and a voice-over, was created by Mr. Beam, a creative studio based in Utrecht, on the occasion of the museum’s 200 year anniversary. In the show, the history of the collection of the museum and in particular of the ancient temple are high-lighted. The tale of the temple is one of the most extraordinary histories to be told in the museum, because, in a sense, the temple still serves one of its most significant purposes: bringing people together.

But the ancient building does more than gathering people together. Its history poses challenges to the Rijksmuseum van Oudheden and its visitors. It constitutes a plea to consider that antiquity cannot be seen separately from modern discourses of power and control, as the Nile Pop event has made abundantly clear. The countries involved in the UNESCO campaign – Egypt included – had particular political motives related to their colonial pasts and the narrative of the temple as a gift in exchange for salvaging archaeology is reductive. Additionally, the temple of Taffa illustrates how we write history today. The sheer description of the building as a temple reveals contemporary tendencies to concentrate on the monumental and the ancient, and to minimise the other roles the structure had in the lives of Nubian people. The displaced Nubian inhabitants of drowned town of Taffa are hardly ever mentioned at all. Although the Rijksmuseum van Oudheden strives to highlight the Nubian character of the temple and its original place in northeast Africa, the building is generally seen as an Egyptian temple. This perspective is rooted in Western thinking of the 19th century and early 20th century that tended to prioritise the study, and hence the cultures, of ancient Egypt over ancient Nubia. The history of Taffa allows us to face these challenges and, as the Nile Pop symposium clearly shows, to widen our scope and to include the larger Nile Valley.

Youtube clip: Light show by Mr. Beam

Selected bibliography

Lucia Allais, ‘The Design of the Nubia Desert: Monuments, Mobility, and the Space of Global Culture’ in: Timothy Hyde (ed), Governing by Design: Architecture, Economy, and Politics in the Twentieth Century / Aggregate (Pittsburgh, 2012), 179-215.

William Carruthers, ‘Multilateral possibilities: decolonization, preservation, and the case of Egypt’ in: Future Anterior: Journal of Historic Preservation History Theory & Criticism 13.1 (2016), 36-48.

Chloé Maurel, ‘Le sauvetage des monuments de Nubie par l’Unesco (1955-1968)’ in: Égypte/Monde arabe 10 (2013), 255-286.

Christiane Desrouches-Noblecourt, La Grande Nubiade, ou, Le parcours d’une égyptologue. Paris, 1992.

Maarten J. Raven, ‘The temple of Taffeh: A study of details’ in: Oudheidkundige mededelingen uit het Rijksmuseum van Oudheden 76 (1996), 41-62.

Maarten J. Raven, ‘The temple of Taffeh, II: the graffiti’ in: Oudheidkundige mededelingen uit het Rijksmuseum van Oudheden 79 (1999), 81-102.

Hans D. Schneider, Taffeh. Rond de wederopbouwing van een Nubische tempel. The Hague, 1979.

Review

On Violence at Taffa/Taffeh

William Carruthers, University of East Anglia

The story of the Temple of Taffeh, as Daniel Soliman’s sensitive article relates, is the story of a “building [that] spans two millennia.” Not simply ancient, this is the story of a place that continues to be written, even as the structure has been rebuilt thousands of kilometres away and the Nubian town that lent the temple its name has been flooded beyond physical repair. This process of (re-) writing also makes uncomfortable reading for those involved in the structure’s preservation, not least because it raises serious questions about the fate of the Nubians who lived there.

As Soliman shows, the documentation and salvage of the temple—always presented as altruistic—came laced with violent moments, both physical and linguistic. Over the course of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, as European travellers visited Taffa with increasing regularity, “such visits sometimes led to clashes with the villagers.” In the mid-twentieth century, when the French Egyptologist Christiane Desroches Noblecourt visited the site ahead of its disassembly, she felt able to describe a protesting Nubian woman “as ‘a sort of sorcerer.’”

What led to such violence? How could Noblecourt—far from alone in her use of such language—justify a description so obviously racialised (and racist). Understanding this situation involves thinking historically, reading between the lines in a way that Soliman’s article does not always have the space to do—and thinking of violence in other forms, too.

As Soliman notes, it can be difficult to move away from “contemporary tendencies to concentrate on the monumental and the ancient” when talking about a place like Taffa. One glance at the illustrations that accompany his article shows why: the product of European explorers and archaeological officialdom, the images show a monumental, Nile-side ruin whose relationship with its inhabitants is one that repeats the familiar Orientalist representation of people deployed as markers of scale.

The archaeological site—and distinct proper noun—of Taffeh, in other words, has a long-term history of separation: visually and linguistically removed from the place—Taffa—of which it was a part, even as the town’s inhabitants literally reused the blocks of the southern of the settlement’s two temples to help build their homes. By the time in the 1960s that the northern temple was taken apart and moved, piece by piece, to Elephantine, there was little likelihood that anyone with the power to do so would dwell on this more complex history. A vision solidified by a thousand tourist guides and archaeological reports, so the Temple of Taffeh had become just that: capitalised, proper, and distinct. Even Soliman refers to “the villagers who lived around the remains of the ancient site.”

It is difficult to undo this opposition between past and present, although Soliman rightly notes the necessity of doing so. Archives perhaps provide one means of understanding the complexity of a place like Taffa, yet only if used appropriately: Nubians should be the primary beneficiary here, and Nubians themselves should direct such work (Carruthers 2020; cf. Agha 2019). Such an outcome, however, presents a further challenge to those who write the narratives of the past that have made somewhere like the Temple of Taffeh seem so familiar. It is a challenge, though, that needs to be addressed.

Bibliography